Today sees the launch of How Connected is national food policy in England?, the second report in the FRC Rethinking Food Governance series. It identifies food system issues where there is evidence of good connections and others where connections could be better. The detailed report is accompanied by a Policy Brief that summarises the findings. In this blog, report author Kelly Parsons explains why connected policy-making is vital for tackling complex, cross-cutting issues such as food – and why it involves not just the alignment of policies but also the ongoing negotiation of goals and values.

January saw the arrival of another chunky food report – Making Better Policies for Food Systems, from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Its message is that more coherent policies hold ‘tremendous promise’ for making progress across the triple challenge of ensuring food and nutrition security, decent livelihoods and environmental sustainability. Policy-makers need to take account of these multiple dimensions, exploit synergies and manage trade-offs between them.

Though the language differs, this emphasis on the need for a ‘food systems approach’ to policy is echoed in other recent reports, such as the Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition’s Foresight 2.0: Future Food Systems: For people, our planet and prosperity. One of its key recommendations is for policy interventions to be designed ‘through the lens of an integrated food system and implemented in joined-up rather than piecemeal ways’ because ‘the steps needed to bring about a successful and meaningful transition are interlocking and mutually supportive, which requires a coherent joined-up approach to the choice of instruments to use and how they are implemented’.

But it’s a tough challenge to translate these broad principles into something actionable, in a landscape where issues cut across many departmental remits and policies, and where evidence on potential interactions is patchy. The European Commission’s Standing Committee on Agricultural Research concluded in its review of food systems research that there is a shortage of studies that take a ‘food systems perspective’. Similarly, the UK Parliament House of Lords wide-ranging inquiry into the links between inequality, public health and food sustainability noted that although the inquiry heard repeated calls for ‘whole system change’, exactly what that change might involve and how it might be realised ‘were issues many organisations are still grappling with’.

In Making Better Policies, the OECD offers some guidance on practical actions governments can take to improve the evidence base on system interdependencies and policy interactions. One obvious but neglected action is a ‘stocktake’ of policies relevant to food systems in a nation or region; this can be followed by a screening for potential ‘interactions’ between these different activities. The first Rethinking Food Governance Report, Who makes food policy in England, showed how a stocktake – an exercise that maps food policy actors and activities – could be done (the mapping was done for national-level policies in England, but it has been replicated for other jurisdictions).

The next step in the Rethinking Food Governance project has been to examine where coordination on cross-cutting food systems issues is and is not currently happening. The findings are presented in the report released today.

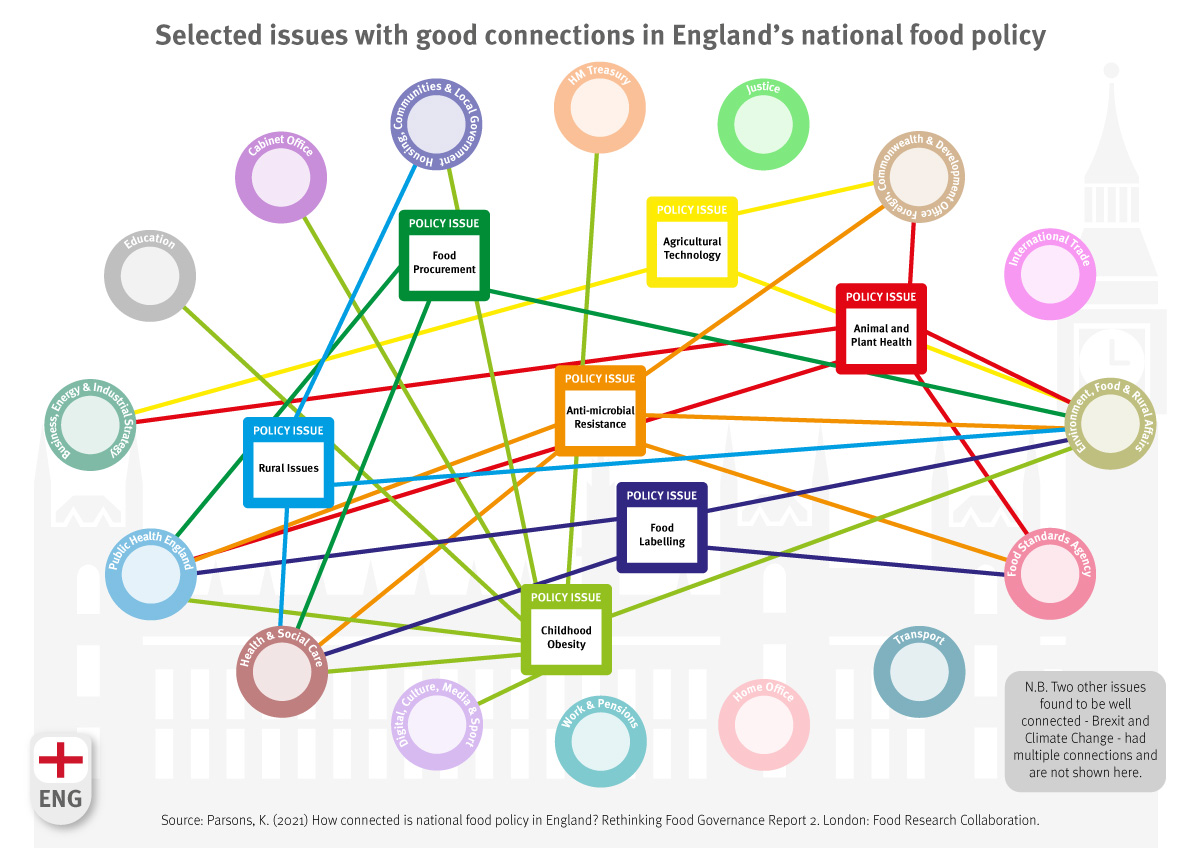

Taking as a starting point food policy activity across government as a whole, the screening process used interviews and documentary analysis to probe where food policy connections are already being made; where connections which could be beneficial are weak or missing; and where underlying tensions mitigate against policy coherence. The report presents the first detailed analysis of how connected food policy is in England – how effectively different parts of the national government are working together on food systems issues that cut across departmental boundaries. The screening identified nine important food policy issues where policy is working (or aspiring to work) in a connected way, including Antimicrobial Resistance and Childhood Obesity (see diagram above).

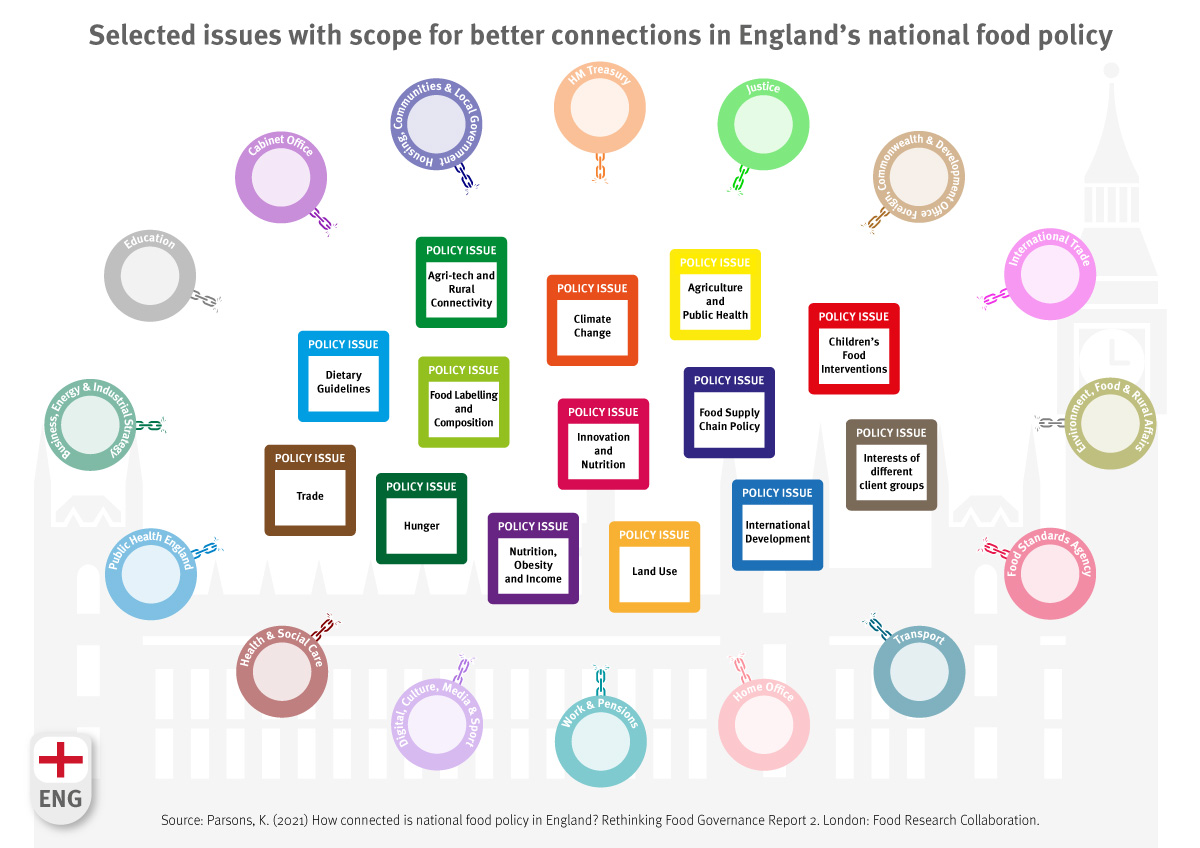

It also identified 14 examples of ‘disconnects’, where food issues were not being connected across government, leading to incoherence, including: Agriculture and Public Health; Climate Change; and Hunger.

The examples in these two diagrams are not presented as a fully-fledged inventory of what’s right and wrong with the current policy approach. Instead, as the OECD suggests, they offer a starting point for further scrutiny, to ascertain how important they are from a policy perspective and whether they warrant adjustment. This process will require efforts to bring together a wide range of facts, interests and values. Along with policy disconnects, the screening highlighted the value-laden nature of identifying where current policy arrangements are problematic, with perspectives grounded in stakeholders’ views of how the food system should be (and ultimately what it is for). There were, for example, quite different perspectives from those working inside government (as civil servants or other officials) and those working on food policy from outside government (in business, civil society, or academia). There is a sense from inside government that external stakeholders don’t understand the realities of policy-making and are looking for ‘utopia’. Conversely, there is a view from civil society groups, for example, that current efforts to coordinate policy-making are just tinkering around the edges, and that what is needed is a more ambitious approach to system coherence, which places health and environment front and centre.

This makes fixing connections a far from a neutral analytical exercise: while some disconnects are logistical, some arise from ideological or political differences. The findings resonate strongly with the OECD’s observations around how technocratic approaches, which see policy issues as essentially technical problems to be solved by evidence and expertise, will be insufficient, given that:

- Evidence describes the way things are, but policy debates involve a consideration of how things should be;

- Policy discussions around food and agriculture are often complicated by misconceptions and unreliable statistics used in public discourse;

- Achieving a reliable shared understanding of policy issues is an important precondition for developing successful policies;

- And that coherence by itself is of little value if policies are not sufficiently ambitious.

This implies that the definition of ‘better’ warrants a strong focus. If the aim is no less than food system transformation, there is a danger that making better connections and coherence in the status quo – for example by ensuring that current activities are connected across government or making existing policies better by choosing smarter policy instruments – is insufficiently ambitious to meet challenges to human and planetary health and improve equity in the food chain. This goal is likely to require a more open and exploratory approach, involving continuous negotiation of different perspectives, in order to gain some kind of consensus on what ‘better’ policies, and a better food system, might look like; and casting the net wider than linking up existing activities in order to uncover connections which are yet to be fully recognised or understood.

Recommendations from the Rethinking Food Governance project on how to support this process include the need for improved communication and transparency around what is happening in government; a more connected approach by civil society and a ‘de-siloing’ of their access to policy-making; increased participation from outside stakeholders; and one or more governance mechanisms to bring actors and activities together to make connections where they are required. Part 3 of the project will address what these governance arrangements might look like.