In the words of our funder, the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, the next phase of the Food Research Collaboration’s job is to ‘protect the interests of the sustainable food sector at a time of substantial change’. The meaning of ‘substantial change’ is clear: we will continue to analyse the food system impacts of Brexit and Covid-19. But the ‘sustainable food sector’ is harder to define.

Most of our subscribers would likely have their own definitions, and there would probably be overlap. The sustainable food sector might, for example, be environmentally protective – or even regenerative. In other words it would not just take care of the natural environment, but improve its condition by restoring ecosystems and reducing damage to climate and biodiversity. It might provide fair (or even generous) prices to farmers and growers, and decent wages to people working along food supply chains. It might supply food to consumers at fair prices (and that might mean – to move beyond the food system – that they would have enough money to be able to afford fairly priced food). It might be geared to supplying foods that support human health – fresh, nutritious, not highly processed, with lots of the vegetables and fruit our diets currently lack – and it might guarantee the humane treatment of all farmed animals. It might seek to minimise waste.

Some people might go beyond this description to highlight the factors that have produced a food system in need of transformation. The scholar Clare Hinrichs summed up the antithesis of a sustainable food system as one that is: ‘large-scale, industrialised, consolidating and increasingly global … outsized, standardised, environmentally degrading, wasteful, unjust, unhealthy, placeless, disempowering’1. On this basis, one might add to the list of desired characteristics: embedded in a locality; non-standardising; strengthening of community links; resistant to consolidation and corporate control; possibly always small-scale. But by now we are moving away from consensus and into more politically contested territory.

Is this a problem? In other words, does the lack of a neat, agreed, summarising term for the kind of food system that many of us would like to see hinder the process of working towards it? Does the label ‘sustainable’ do the job? The term has been derided for meaning everything and nothing, which undoubtedly allows it to be subverted for unsustainable purposes. And what about companies like Unilever and Marks and Spencer, large corporations that have gone to considerable lengths to ‘green’ their business practices and supply chains? Are they to be included in the sustainable sector? (Answer: for the FRC’s purposes no, they don’t need our help. But many definitions of sustainable would not exclude them.)

Another problem is that the sort of food system being outlined here is often defined as the ‘alternative’ to the one described by Clare Hinrichs. The label ‘alternative food systems’ (or AFS) is probably as widely used as sustainable food systems (SFS), but it has a lot of baggage: it can have unhelpful connotations of contrarianism or eccentricity (one of the first alternative restaurants in London was actually called Cranks). More damagingly, the term accepts a position of marginality: this kind of food system will always be subsidiary to the (by implication) main, dominant legitimate one that we need to feed large populations — the one that is large-scale, industrialised, etc. The term ‘alternative’ thus normalises industrial food systems.

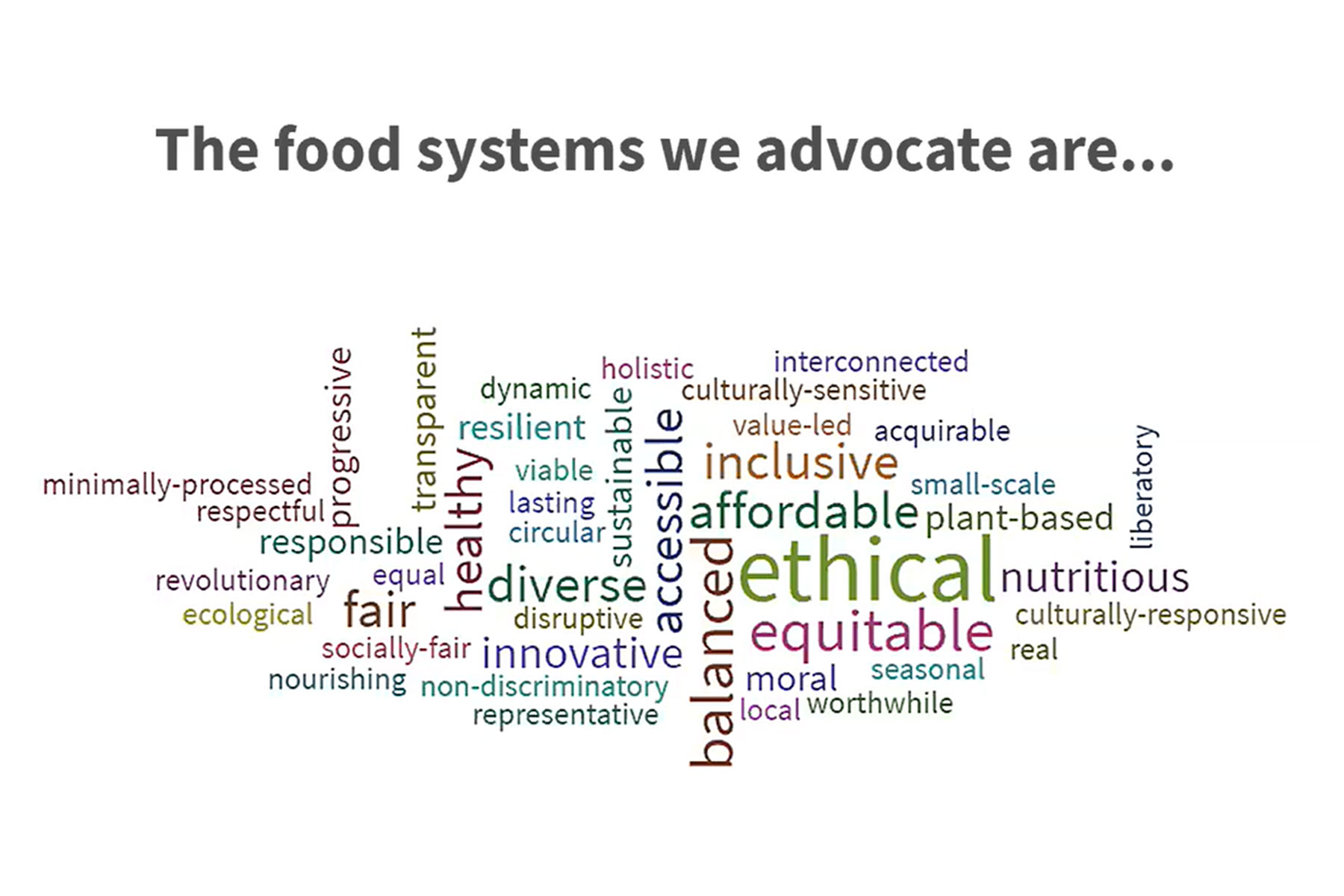

We asked: when you think of the food system you want, what attributes does it have? And what label would you use to sum this kind of food system up?

To help us think all this through, we recently asked a group of students on the Centre for Food Policy’s Master’s course (19 women, on the evening in question) to provide some insights. We asked: when you think of the food system you want, what attributes does it have? And what label would you use to sum this kind of food system up? The wordclouds reproduced here represent their answers. The students wanted food systems that were, among other things, healthy, equitable, inclusive, affordable, nutritious, culturally sensitive, sustainable, circular, resilient, respectful, lasting and simply ‘real’. And to sum these attributes up, the preferred labels included ethical, innovative, interconnected, worthwhile, progressive, revolutionary and balanced.

When the rural sociologist Jack Kloppenburg asked a similar question twenty years ago to a group of delegates at a food conference in the USA, he elicited a not dissimilar range of adjectives, including: relational, proximate, diverse, ecologically sustainable, economically sustaining, just, ethical, healthful, participatory and culturally nourishing2.

There are shared values and goals here, both within and between groups, though a striking difference is the students’ urgent sense of the need for change, conveyed by their choice of the word ‘revolutionary’. But even within the two sets of definitions, there is a lot of breadth and diversity. When we use the term ‘sustainable’ in relation to the food sector, we are asking it to do a lot of work.

Nevertheless, it has advantages. One is that it possesses a now-accepted framing3 that brings together ecological, social and economic concerns. We need coherent policies to link these, looking for ‘double dividends’ and recognising trade-offs. And it also captures what has been called the ‘the great contribution of the word “sustainable”’: the issue of time4. It obliges us to think about the future impacts of our activities as well as the past and present ones.

So the FRC will continue to look out for the ‘sustainable food sector’, highlighting policies that provide opportunities or tilt the playing field against it. And in this we will be guided and inspired by our students’ aspirations.

[1] Hinrichs, C. 2010, “Conceptualising and creating sustainable food systems: How interdisciplinarity can help” in Imagining sustainable food systems: Theory and practice, ed. A. Blay-Palmer, Ashgate, Farnham, Surrey, pp. 17-35.

[2] Kloppenburg, J., Lezburg, S., de Master, K., Stevenson, G.W. & Hendrickson, J. 2000, “Tasting food, tasting sustainability: Defining the attributes of an alternative food system with competent, ordinary people”, Human Organisation, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 177-186.

[3] World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987, Our Common Future (The Brundtland report), available at https://www.are.admin.ch/are/en/home/sustainable-development/international-cooperation/2030agenda/un-_-milestones-in-sustainable-development/1987–brundtland-report.html

[4] Harris, J.M. & Goodwin, N.R. 2001, “Volume Introduction” in A survey of Sustainable Development: social and economic dimensions, eds. J. Harris, T. Wise, K.P. Gallagher & N.R. Goodwin, Island Press, Washington / Covelo / London, pp. xxvii-xxxvii, P. xviii.