Another year around the sun, and many of the same problems remain. Permacrisis – the Collins Dictionary 2022 word of the year – will remain the zeitgeist in 2023, as the war in Ukraine, soaring inflation, widespread industrial action, and inadequate outcomes from international climate negotiations continue to play out.

But findings from Tortoise Media’s Responsibility100 Index signal we are not all in this together.

It found that CEOs in the FTSE 100 Index – which lists the UK’s largest publicly-owned companies – were paid 30% more in 2022 than in 2021.

Meanwhile only two out of eight food companies in the Index – Unilever and Diageo – paid their employees the real living wage, compared to 46% of all FTSE 100 companies.

Unilever and Diageo were also the most profitable food companies in the Index, which could indicate a link between paying fair wages and productive business operations.

Furthermore, last year’s Tortoise Better Food Index found that only two of the 30 largest food companies in Britain paid the real living wage (Nestle and Unilever), as per the Living Wage Foundation’s recommendation of £11.95 in London and £10.90 outside of London.[1]

The gap between CEO pay and the average worker is particularly egregious in the food sector, and is widening over time.

Take Tesco’s CEO, Ken Murphy. He earned £4.74 million last year – which includes the highest annual bonus awarded by the supermarket since 2016 – making his total pay 224 times that of the average member of staff at Tesco.

The average employee at Tesco has an annual income of £21,217– about £4,000 less than the minimum acceptable standard of living, according to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.[2]

Sainsbury’s was hardly any better, with CEO Simon Roberts paid 183 times more than the average worker at the company.

As CEOs receive handsome pay packets, the majority of workers underneath them have suffered from low wages and a proliferating cost of living crisis.

A 2021 survey from the Bakers, Food and Allied Workers’ Union found that one in five food workers in the UK are in food poverty.[3] Its general secretary, Sarah Woolley, writing in Tribune, said, “the very people going out to work in food factories and shops to keep shelves stocked and fridges filled are coming home to find their own cupboards are bare”.[4]

Soaring inflation is making things worse. Annual food inflation jumped to 13.3% in December, up from 12.4% in November – the highest monthly inflation rate on record, according to the British Retail Consortium and the data firm Nielsen.[5] And inflation rates were highest in the fresh food category – at 15% in December 2022 – which further fuels the cycle of deprivation between low incomes and poor health outcomes.

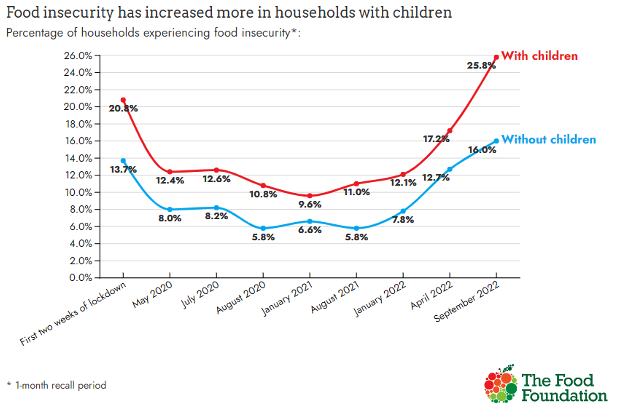

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) found one in seven people across the UK (14%) are skipping meals because they can’t afford essentials.[6] And the Trussell Trust saw record numbers of people seeking help last year, with 320,000 turning to the charity’s food banks – a 40% increase in comparison to the previous year.

Notoriously tight profit margins are often to blame for low wages in the food sector. For example, poultry producers are among the least profitable businesses across Britain’s food industry, averaging at 2.7%. They also have some of the lowest wages, according to Tortoise’s Better Food Index.

Tight profit margins exist because of bullish price-competitive strategies employed by supermarkets to make their own-label goods the best value for money. Own-label producers like Samworth Brothers and 2 Sisters Food Group bear the brunt of the strategies, and as a result, have profit margins of -2.72% and 0.96% respectively.

However, the answer to supporting those on low incomes isn’t to make food cheaper. Products that cost less in monetary terms often have a higher cost elsewhere, such as in climate and animal welfare.

Increasing wages should be a priority for the food sector but it will require transformation at the system level.

The Tortoise Better Food Index will be updated later this year, and will interrogate how affordable, sustainable and ethical our food is in the UK. It ranks the 30 largest food companies in Britain on their ‘Talk’ and their ‘Walk’ in relation to creating a better food system for all.